From farmers to clickworkers

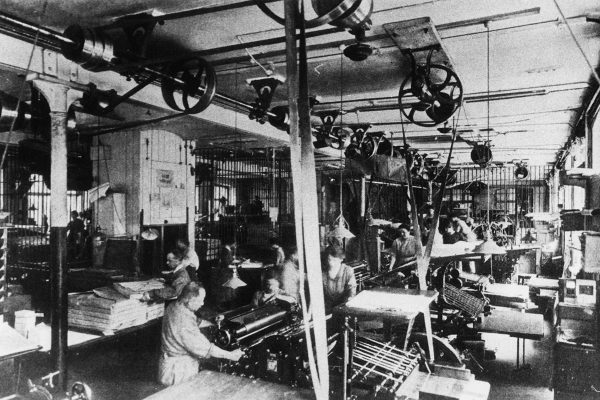

Until the 19th century, most people worked in their own family businesses, often in agriculture and trade. With industrialisation at the beginning of the 20th century, the working environment changed fundamentally for the first time. Factories were built and more and more people worked there. This also had legal consequences. In 1919, the International Labour Organization (ILO) was founded, today a specialised agency of the United Nations Organization (UNO), whose mandate is, among other things, to protect the rights of working people. The ILO has created international standards of labour law, which have been transferred into the law of the member states via Conventions.

In recent decades, freelancing has developed, especially in the field of marketing and IT, in which contractors work independently for companies. In this way, companies acquire missing know-how on the one hand and workers on the other, whom they can deploy on call and thus in an absolutely flexible manner. Recently, clickworkers (see below) have joined this development. What is special about these employment relationships is that, on the one hand, people work like freelancers (see below). On the other hand, they are integrated like employees into the system of an internet platform, such as that of the ride service provider Uber (see below), as soon as they click into the system. While freelancers can be relatively well covered by the existing law, clickworkers somehow no longer fit into the system. They feel self-employed, act largely as such, but, as in the case of Uber, are nevertheless integrated into digital systems. The question arises whether new law needs to be created for this new type of employment relationship (see below). Given the current development of employment relationships, it can be assumed that in the future most employees will no longer work as salaried employees, but as self-employed persons or in click jobs (s. NZZ 28.01.2018 Verabschieden Sie sich von Ihrer festen Stelle).