The task of antitrust law (CH: Cartel Act, CartA) is to prevent competition from cooling down, especially through cartels and mergers. In other words, antitrust law aims to heat up competition.

The responsible authority for the supervision and enforcement of antitrust regulation in Switzerland is the Competition Commission (COMCO).

Already in the purpose of CartA 1 it is stated that only practices that are harmful to the market are not permissible according to antitrust law. Based on this principle, it is therefore even possible that a cartel is assessed as permissible by the COMCO, even though it restricts the market, because it effectively has no negative, even positive effects on the market. This was long claimed, for example, of the Swiss book cartel, in which publishers fixed book prices with booksellers. The proponents of the cartel claimed that the generally higher prices resulting from the cartel promoted a diverse book market because publishers and booksellers could, for example, use the overly expensive bestsellers to cross-subsidise books that did less well but enriched the book offer (e.g. poetry, expensive photo books). The COMCO banned the book cartel in 1999. In 2012, the people rejected the reintroduction of the book cartel in a referendum by means of the Federal Law on Fixed Book Prices (see www.bk.admin.ch/ch/d/pore/va/20120311/index.html).

According to CartA 2, the rules of antitrust law apply to the behaviour of all companies under private and public law. All demanders or suppliers of goods and services in the economic process are considered undertakings, regardless of their legal or organisational form.

Antitrust cases

The law generally distinguishes between three main cases of cartelistic behaviour.

Agreements restricting competition according to CartA 4 I and 5 are legally enforceable or non-enforceable agreements as well as concerted practices of undertakings at the same (horizontal agreements; commonly referred to as “cartels”) or different (vertical agreements) levels of the market which have as their object or effect the restriction of competition. According to the law, if such agreements exist, it must be presumed that they effectively eliminate the market. However, the market participants concerned can prove that this is not the case because the agreements have positive effects on the market (economic efficiency, CartA 5 f.; see also the case of the book cartel above).

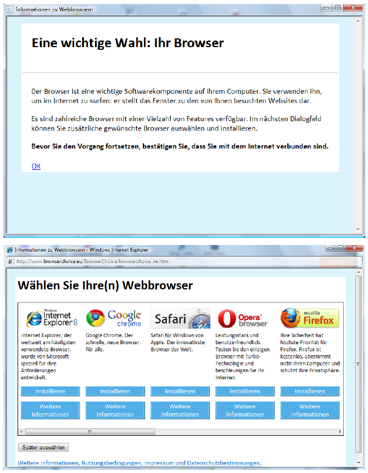

Undertakings with a dominant position pursuant to CartA 4 II are subject to the permanent risk of abusing this position within the meaning of CartA 7 (s. below). A dominant company is defined as one or more companies that are able to behave independently of other market participants (competitors, suppliers or customers) to a significant extent on a market ( CartA 4 II). According to CartA 7, it is not market dominance that is inadmissible, but its abuse. An illustrative example of the abuse of a dominant position is the case of Microsoft‘s Internet browser. Even though the market share of Microsoft’s operating system has declined in recent years, Windows is still running on over 90 % of desktop systems at the end of 2017 (s. e.g. www.borncity.com). Because internet browsers are also installed via the operating system as a gateway to the internet, the EU Commission obliged Microsoft in 2009 to set up a pop-up during the installation of the Windows operating system in which the user is given the option of installing one or more browsers other than or alongside Microsoft’s internet browser «Internet Explorer» (now called «Edge»). In 2013, the EU Commission found that Microsoft had not fulfilled this requirement or had not fulfilled it sufficiently and subsequently fined Microsoft 561 million euros (sic!) on the grounds that Microsoft had abused its market power in the area of operating systems or internet browsers (s. e.g. Spiegel Online 06.03.2013 EU fines Microsoft 561 million euros).

Mergers form the third antitrust case. According to CartA 4 i.c.w. CartA 9, mergers with a certain turnover volume must be reported to the COMCO. The COMCO then examines whether the merger in question restricts competition to the detriment of consumers or suppliers (s. above). If this is the case, the COMCO can either prohibit the merger or allow it under certain conditions. An interesting example of this is the purchase of the Swiss retail company Denner by the Swiss retail group Migros. In 2007, to the astonishment of many, the COMCO approved this merger, but under certain conditions, in particular Migros and Denner were obliged to procure goods intended for resale separately. The COMCO based its positive decision essentially on the fact that competition in the retail trade, especially from the numerous foreign suppliers who were already active in the Swiss market or would be active in the future, was so great that the merger of Migros and Denner would have no significant or negative effect on this competition. The development since 2007 has obviously confirmed this, in particular retail prices have fallen constantly. (s. also COMCO Info 04.09.2007).

Antitrust proceedings

In the event of a suspected violation of the Cartel Act, it provides for three possible procedures. Firstly, affected market participants can take legal action against the alleged infringer before a civil court pursuant to CartA 12. KG. However, the COMCO may also initiate administrative proceedings on its own initiative or upon notification pursuant to CartA 18 ff.. Within the framework of these administrative proceedings, the COMCO can itself impose sanctions against cartelistic behaviour. And these are serious! In the case of unlawful restraints of competition, the fines can amount to up to 10 % of the turnover of the last three years in Switzerland. In particular, for violations of orders against decisions of the COMCO, actual criminal sanctions are also provided for under CartA 54 ff..